U.S. Coast Guard rescue crews constantly train, interchangeable to always be ready to save lives

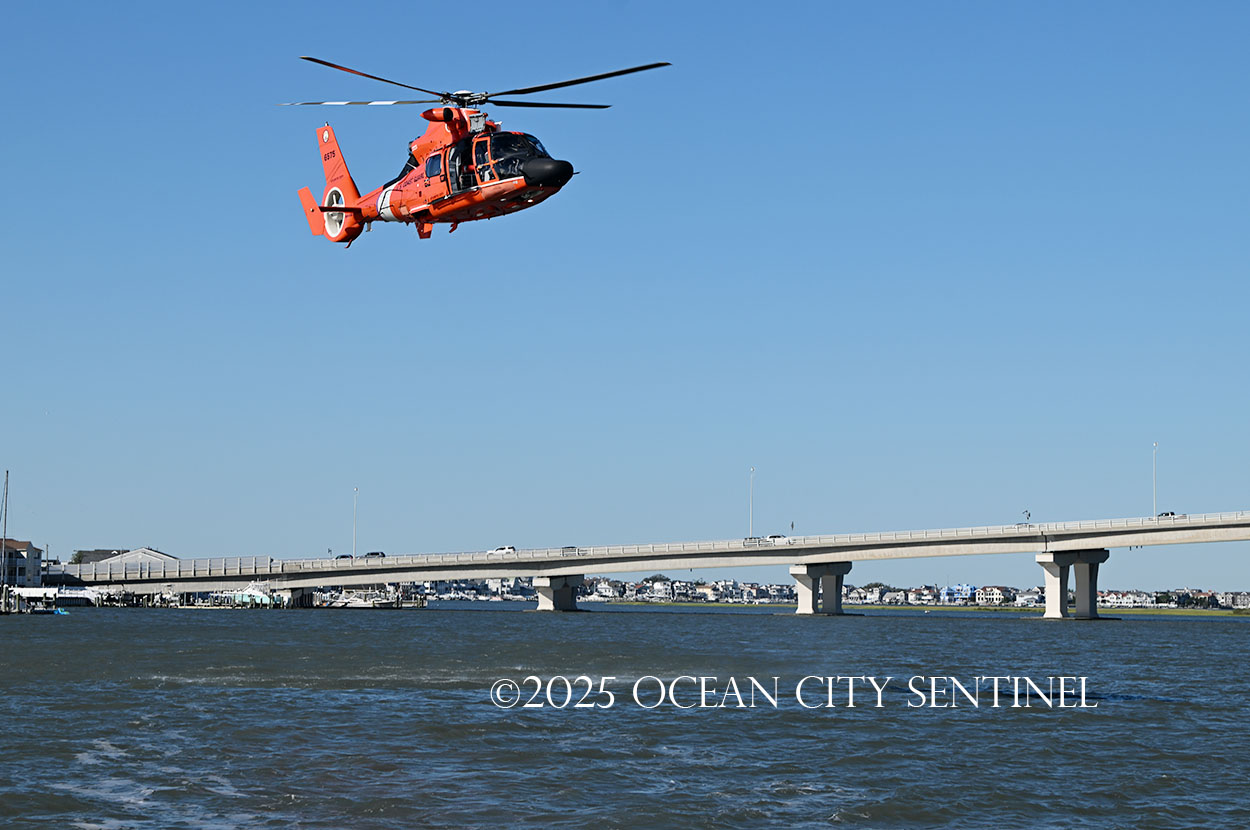

EGG HARBOR TOWNSHIP — The crews on those bright orange U.S. Coast Guard helicopters ever-present above the Jersey shore are like interchangeable parts. They are ready to go no matter who happens to step in as a pilot, flight mechanic or rescue swimmer.

They have to be fully prepared to work with any crew member to live up to the Coast Guard’s motto, Semper Paratus — Always Ready.

There are four people on the crews when they are doing rescues — two pilots, a flight mechanic and an aviation survival technician (AST), who is the rescue swimmer.

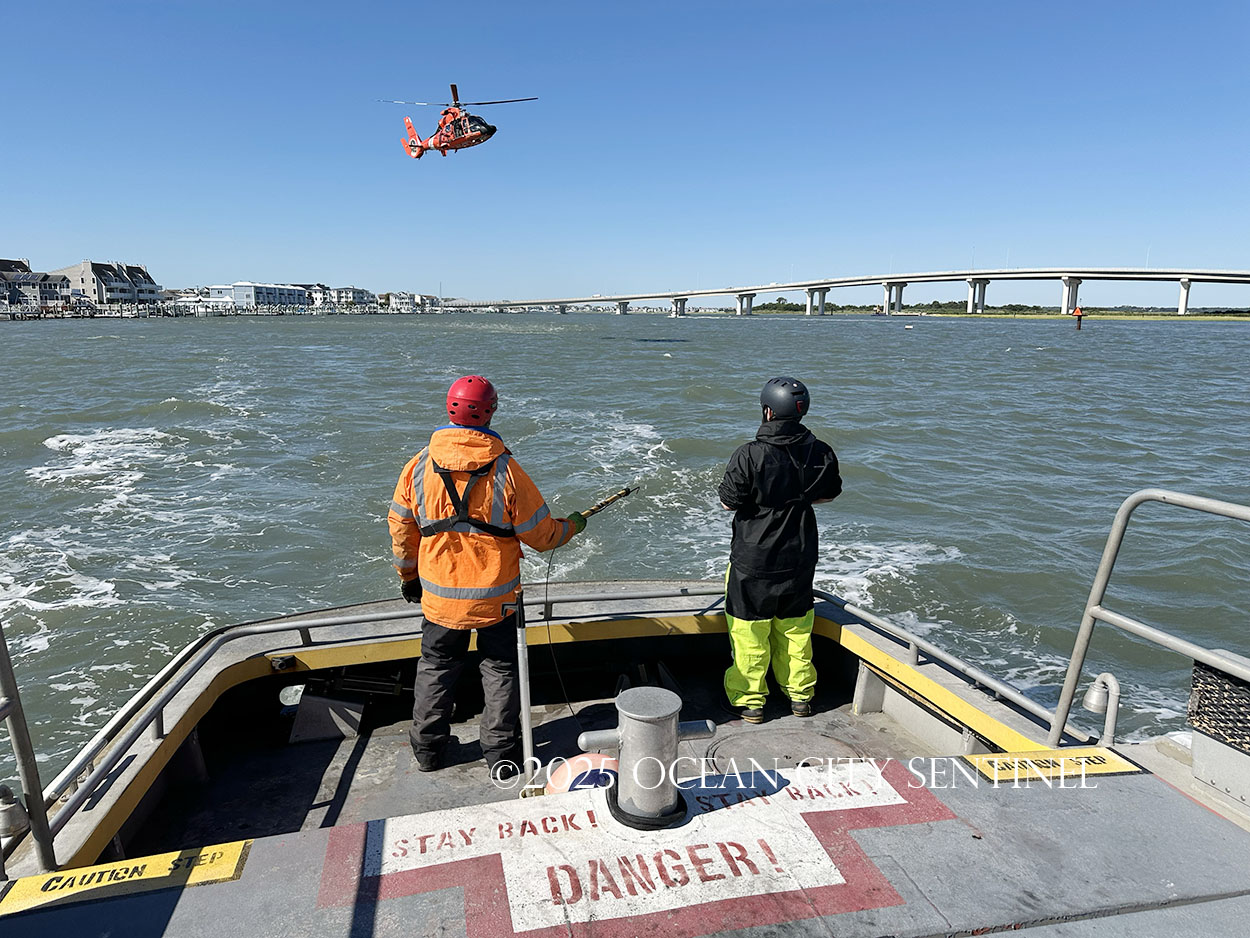

During an August training exercise in the back bay of Ocean City in conjunction with lifeguards from the Ocean City Beach Patrol, the crew included pilot Lt. Sabrina Monaco, who grew up in Jacksonville, Fla.; flight mechanic Adam Timberlake, originally from Maine; and rescue swimmer Conor Plasha, of Ocean City, N.J. They are based at Air Station Atlantic City, which in spite of its name is located at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) complex in Egg Harbor Township.

The trio explained the teamwork necessary to conduct rescues.

The two pilots in the HC-65 Echo helicopters can do pretty much the same things, according to Monaco, but the one in the right seat does most of positioning for hoisting of the rescue swimmer and rescue basket because of the visuals from that side.

One of the pilots always acts as a mission commander, fully responsible for the whole evolution of the mission. She is in constant communication with the flight mechanic, the crew member at the open door who operates the hoist.

“Adam is like the quarterback. He’s calling the shots. He’s driving, I’m flying,” Monaco said. “I’m just listening to him, to what he tells me to do and where he wants me to be.

“We want to set (flight mechanics) up so they have the perfect visual to lower the device or the swimmer,” Monaco said.

She pointed out that on training the crews don’t always take a swimmer if a lift isn’t part of the training or if they’re doing things such as waterway patrols.

But doing the lifts with the swimmer, in practice or during actual rescues, is “exciting,” Monaco said.

Depending on the time or day or conditions, “it could definitely be more serious and a little more daunting,” she said, “but we do a ton of training. We prepare for cases. A lot of things we do are very standard. We have the same checklist, we have the same procedures we go through … keeping things safe and centered.”

Monaco said the team does a lot of low-risk, high-frequency events, but there are those high-risk, low-frequency events sometimes.

“Those are the more extreme situations where something is really risky, the mission is complicated and we don’t do it very often,” she said.

“We want to practice. We want to be comfortable in complex situations so when the search rescue case does happen, you’re not as nervous because you’re prepared,” Monaco said. “It’s different when a person’s life is on the line, obviously, so that adds a level of complexity, but a lot of the lives we save, the process of doing that isn’t that different from what we’re training for every day.”

“It becomes second nature,” Timberlake said, “especially at 3 a.m. when you’re out there.”

Plasha added that there is the routine training for the rescue lifts from the water or from boats, but they also plan for other contingencies. The day before was urban search and rescue training at a fire department’s training tower.

“It’s pretty much their burn building, but we use it to practice for if a hurricane came through and we were rescuing people off of roofs or out of windows,” Plasha said. That type of training isn’t as frequent, “but it’s still important that we feel comfortable and know what we’re doing and have that background.”

Monaco pointed out the standardization for the training for the rescue crews is critical because of the different personnel involved.

Plasha said the group that was on the training mission might not be together again for months. Their roles are designed to be uniform not just across the unit at Air Base Atlantic City, but across the entire Coast Guard.

“It’s like a script and a choreographed dance we are doing as a crew, so any pilot can fly with any flight mechanic and another rescue swimmer around the whole country,” he said. “That’s our strength as a Coast Guard. When a hurricane happens like Harvey or Katrina, we’re able to pull resources from everywhere around the country … and it’s just the same. It’s normal.”

Monaco said she didn’t grow up in a military family, but like Plasha, a former Ocean City Beach Patrol guard, she was a beach lifeguard growing up Florida. She would see the Coast Guard helicopters fly by and thought it looked cool.

“I didn’t grow up always wanting to be a pilot, but I was interested in it,” she said. “It’s just very rewarding. The saving lives aspect of it is really cool and we really train hard and we do a lot of hard things, but at the end of the day, being able to be there for the worst day in someone’s life … I mean, ‘We got you.’”

The AST, when he’s not taking care of the aviation life support equipment at Air Station Atlantic City, is on regular training flights with the rest of the crew because they all have to hit minimum practice requirements on different aspects of rescues, such as hoisting rescue swimmers.

Timberlake, the flight mechanic doing the lifting, said his job is “awesome.” Although he is the guy seen hanging out of the helicopter door operating the hoist (tethered to the helicopter by the “gunner’s belt”), he points out the mechanic part of the job is real.

Just like the rescue swimmers take care of equipment when they’re not flying, Timberlake takes care of the helicopters.

“We’re still maintainers,” he said. “We fix the aircraft, which is unique to the Coast Guard. We fix and fly.” In other branches of the military individuals have specific tasks; there are mechanics who fix aircraft but never see foot inside when they’re in the air.

“I’m also going to be flying on it, so I’m going to make sure I’m doing it right,” Timberlake said.

“We go out in some crazy weather, some crazy seas, and you put them (the swimmers) down, and you’re like, ‘Good luck, Conor.’ And it’s incredible to watch them go,” he said.

“And we have the full trust from up front. We’re telling them (the pilots) where to put the aircraft. … If I say something wrong, it could jeopardize the whole crew, especially Conor out there, out on the hook. I don’t want to be dragging them across the water,” Timberlake said. “It’s intense. It’s fun. You can’t beat it.”

He reiterated what Monaco said about being in constant contact with the pilot. Timberlake said there are not a lot of long pauses between the two.

“There’s a direct correspondence from my voice to her controls, so it’s staying cool, staying calm and painting that picture,” he said, because he has the best view of what’s below them.

Monaco noted before they did the training demonstration with the lifeguards on the bay, they had the lifeguards visit the air station to do pre-planning to ensure their safety. That included the lifeguards operating the jet skis and how they would get the guards into and out of the water.

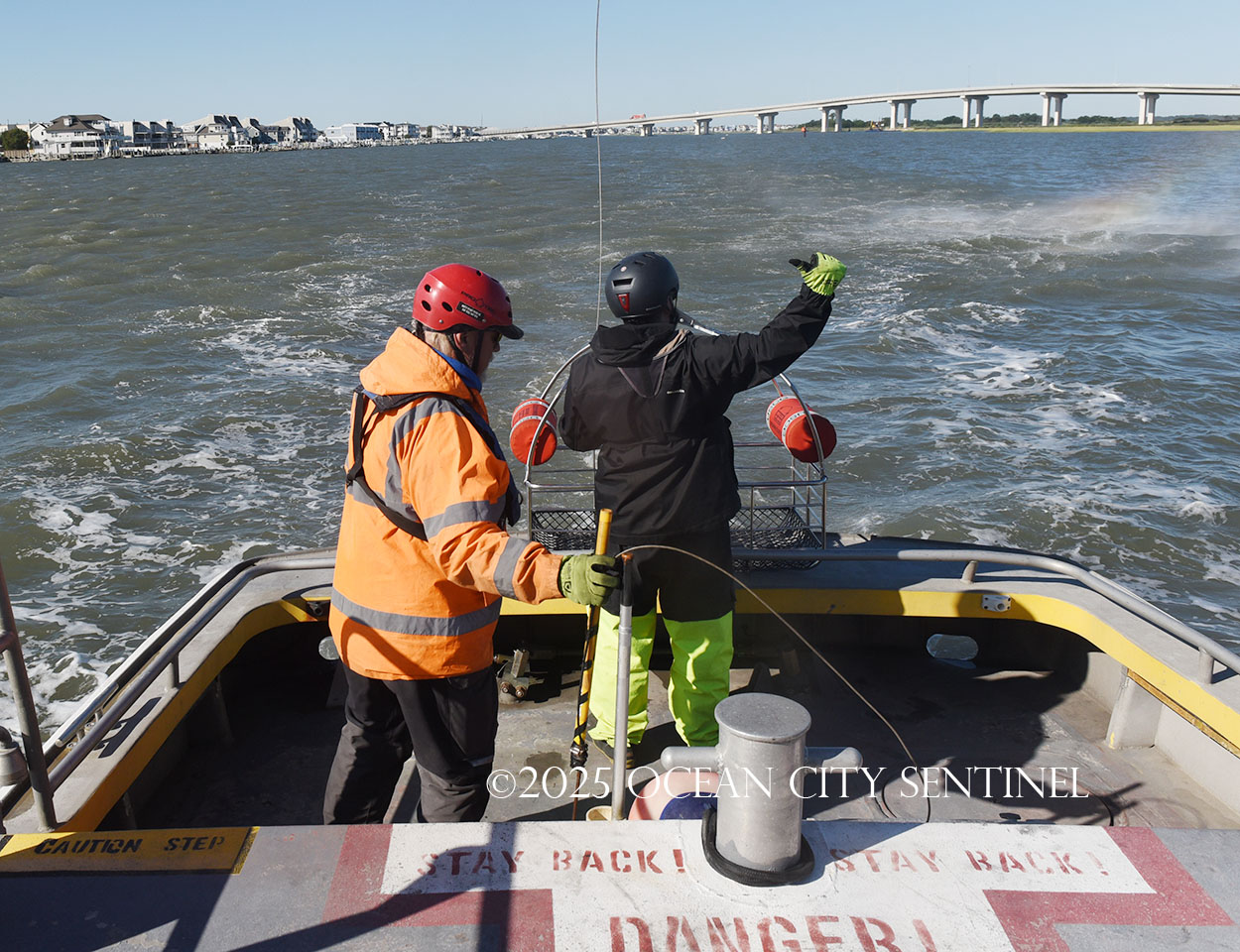

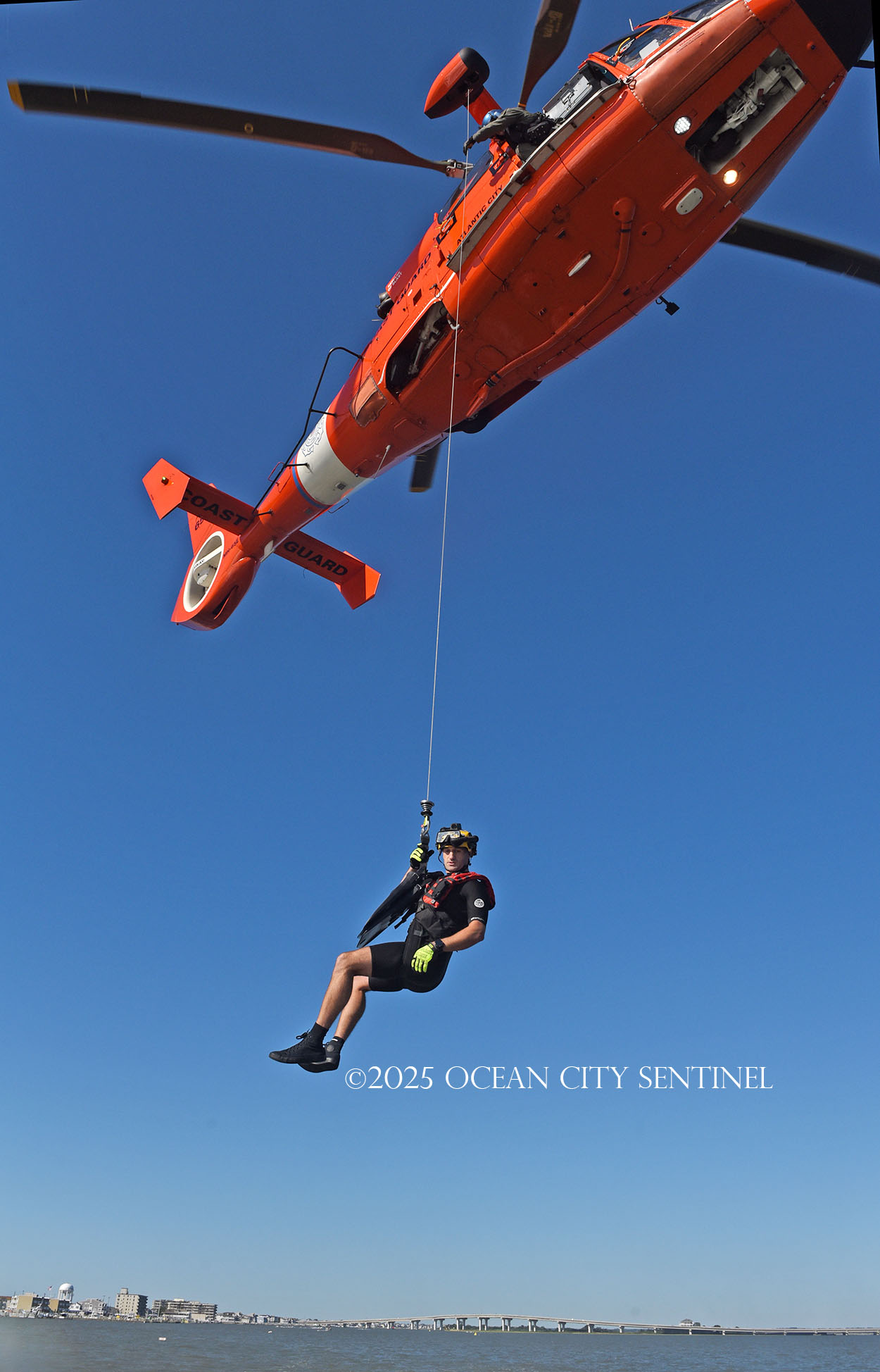

During the demonstration, Lt. Matt DiMarino, Lt. AJ Oves and Deputy Chief Dan Casey all portrayed people needing rescue. Plasha was lowered from the helicopter into the water and then Timberlake lowered a basket.

Plasha “rescued” the guards, just like the guards rescue swimmers in distress off the beach. He pulled them over to the waiting basket and got them safely inside. Plasha hung on as the basket began to lift the guards (one at a time), then let go and dropped back into the water as Timberlake hoisted each of them up. Monaco kept the helicopter steady in position, the noise of the engines a roar and the blow from the propeller churning the water below.

The lifeguards were lifted the 40 feet until they were just outside the door of the helicopter, where Timberlake greeted them before lowering them back to the water. (See related story about their reactions.)

Plasha, who went through the rigorous training to become a rescue swimmer (see related story), noted how Timberlake was impressed with him as a swimmer.

“I think that about the whole air crew because all of us have our specialty and we cannot do what we do without the four people in that group,” he said.

“We have a lot of planes in heavy maintenance right now and they’re literally torn apart and ripped apart and they somehow rebuild them and then I do and fly in it later,” Plasha said. (He wasn’t exaggerating. Providing a tour of the hangar for the reporter, there were multiple helicopters in various stages of (dis)assembly while others were out and ready on the tarmac.)

“It’s crazy to me. I could never personally do that. I wish you could hear them in the helicopter and everything they have to do,” he said about the other crew members. “The amount of buttons up in that cockpit is wild.”

In addition to being a flight mechanic, Timberlake is an instructor, the guy who teaches the other flight mechanics.

“Adam is like a superhero,” Plasha said. “He knows everything.”

Timberlake said if there’s a light on, the pilots will tell him, but they also know the systems so well they diagnose it together and if it’s a problem, whether it’s time to head for home or to land immediately.

“Having someone knowledgeable and backing you up is the best,” Monaco said. Although all the flight mechanics are fully trained, having the experienced instructor aboard, she added, “is amazing.”

“Just like everyone has their role, I think what is super cool is that we all fully appreciate and acknowledge what everyone in that crew does and that’s probably why we work so well as a team. Not just us, but air crews in general. We all have our role and are all experts at our tasks and really what makes everything work,” Plasha said.

As the rescue swimmer, Plasha added, he gets a lot of the limelight, but wants to shine that light on his crew mates.

Understating his own role just a bit, Plasha added, “I just sit in the back and look out the window.”

By DAVID NAHAN/Cape May Star and Wave