Volunteers help Fish & Wildlife track ancient, keystone species

CAPE MAY COURT HOUSE — With the backdrop of a beautiful sunset over Delaware Bay on a quite warm mid-June evening, mosquitoes and biting flies were pestering some 75 volunteers gathered at the narrow Kimbles Beach.

Volunteers were taking in instructions about the creatures with an ancient history that were overcrowding the shoreline just feet away.

Heidi Hanlon, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service stationed just up Kimbles Beach Road in the Cape May National Wildlife Refuge, was telling the group about the horseshoe crabs they would be tagging after sunset.

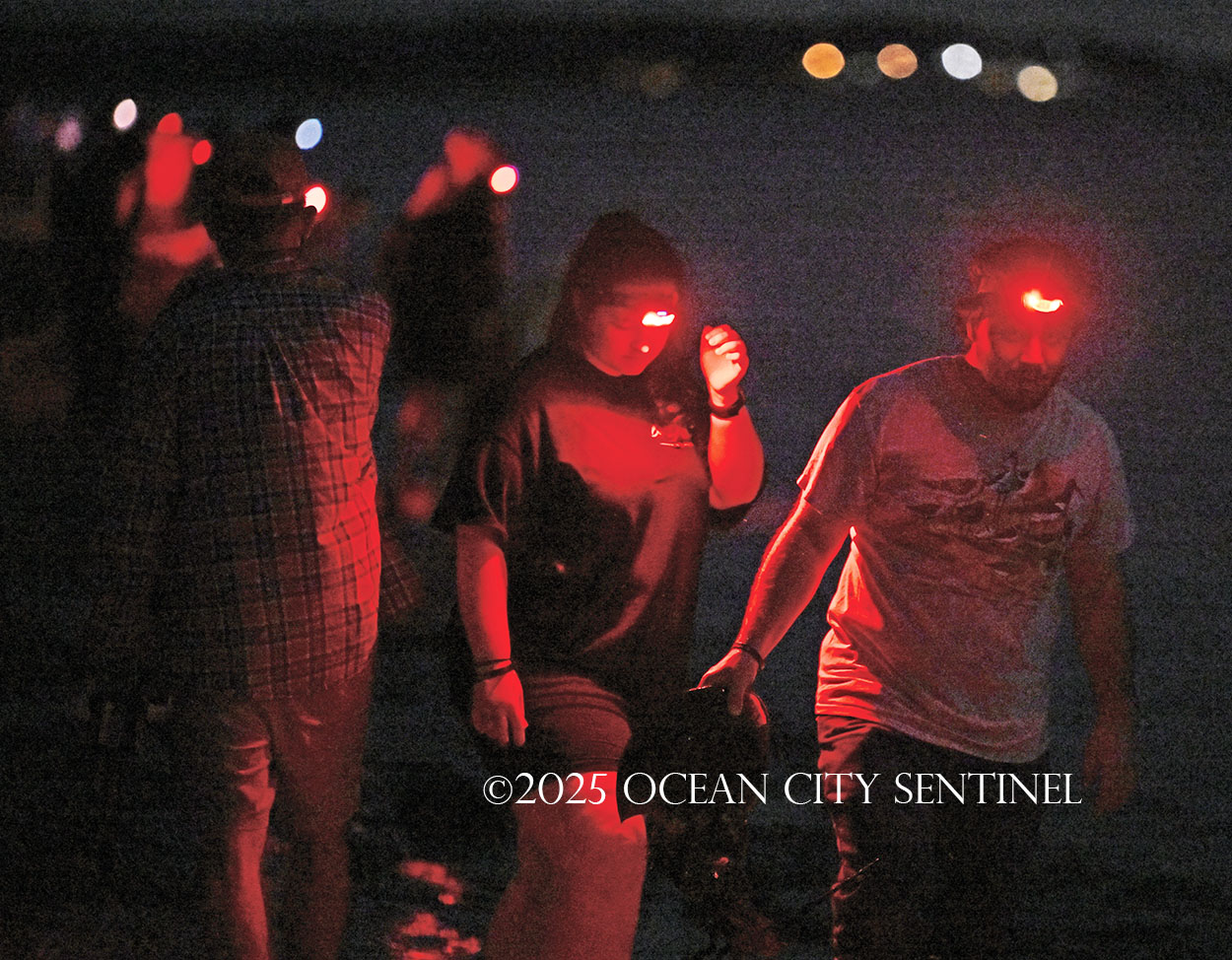

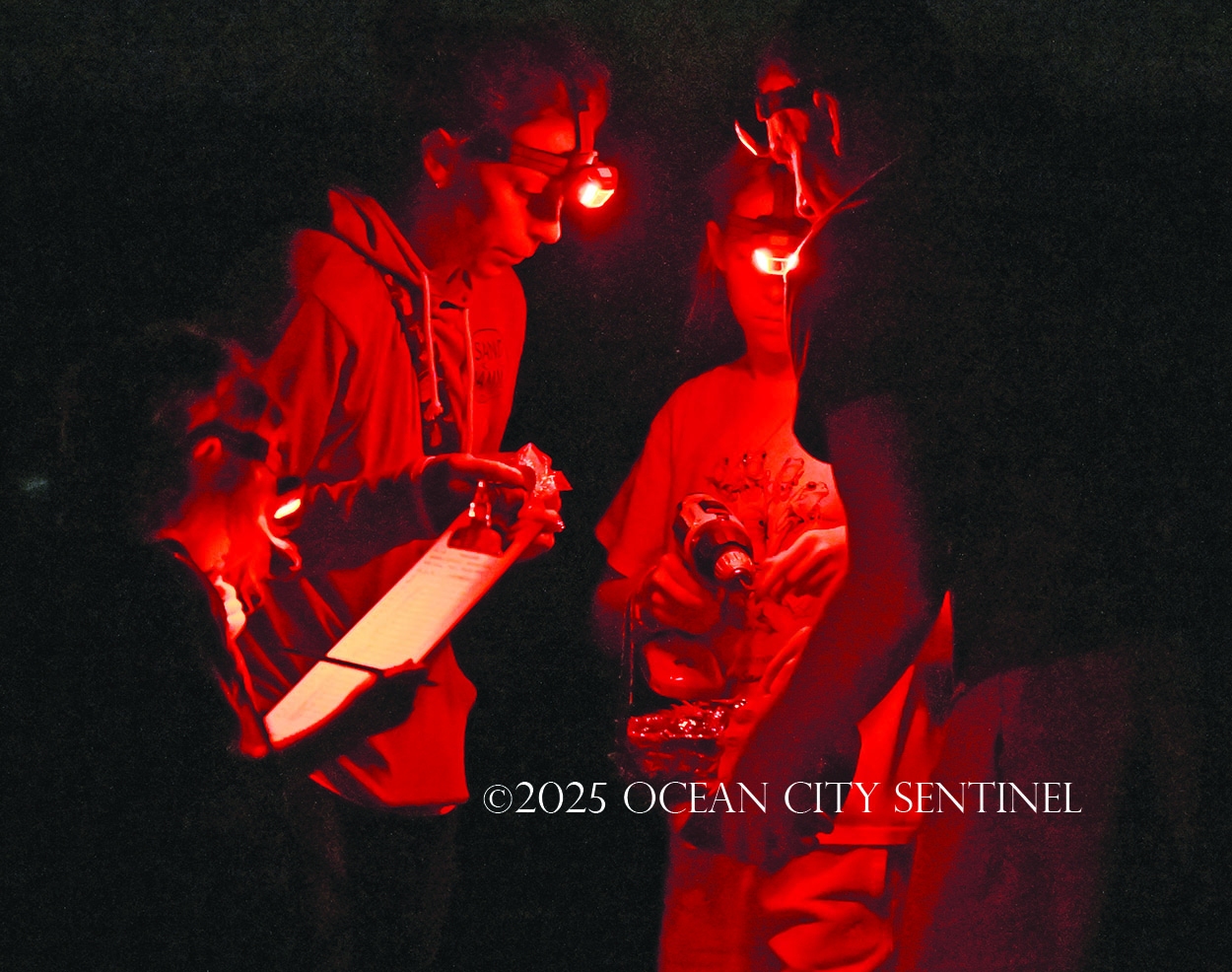

Wearing headlamps with red filters, volunteers of all ages listened as Hanlon explained how each group of four to five would pick up the horseshoe crabs, take down information on size and gender, carefully drill a hole in a corner of their shell and affix a white tag about the size and shape of a quarter. Volunteers were told to be careful not to disturb the horseshoe crabs that had literally hooked up to mate in the shallow water and just onto the sand.

It was an interesting sight after the sun set June 10, the day before the full moon — known in June as the Strawberry Moon. After getting their marching orders on this, the second tagging of the season after one in late May, the groups of volunteers spread out over about a half-mile of shoreline, visible only by the little red lights on their heads.

A line of red dots appeared in the distance under a fairly dark night because the moon was partially obscured by clouds. Volunteers’ features became discernible only upon approach as they happily and quietly used electric hand drills with tips dipped in alcohol between tagging.

One volunteer would pick up and hold the crab, one would do the quick drilling, one apply the tag and another take down the size and gender information related to the specific crab and tag, though duties could shift among them.

Horseshoe crabs

Horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) have been on Earth for 400 million years, according to New Jersey Fish and Wildlife. Beach-goers here in southern New Jersey often see a few of these “living fossils” during their summer visits. (To pick one up stranded in the sand, grasp it by the shell near the head — never the tail — and place it near the water’s edge.)

Horseshoe crabs have 12 legs — five pair for walking and a set of tiny pinchers — and a long, spiky tail used for navigation and to right itself if it flips over. They are brown to gray in color, are 3.5 to 33 inches long, range along the Atlantic coast and are more related to spiders than crabs.

They are scavengers that feed on sea worms, small mollusks, crustaceans and decaying matter on the sea floor. The females are generally much larger than the males.

The largest concentration of breeding horseshoe crabs is along Delaware bay; a moratorium was imposed on their harvest in New Jersey in 2008 after harvests in the 1990s created large declines in the species’ population, which has since recovered, according to Fish and Wildlife.

There is an exception for biomedical companies that can catch horseshoe crabs and withdraw some of their blood, then return them to the bay. The blood is used to produce limulus amebocyte lysate, which is used to detect endotoxin contamination of injectable drugs and implanted devices.

Females can lay 60,000 to 120,000 eggs in batches of a few thousand at a time. Those eggs are a key part of the ecosystem, providing food and energy for migrating shorebirds, which is one reason the horseshoe crabs are considered a keystone species because of their part in the environment.

“The Delaware Bay is such a phenomenon. The crabs and the birds are here at the same time,” Hanlon said. “The crabs spawn and lay their eggs and then the birds come in and feed on the eggs that are on the surface that wouldn’t have hatched. When that’s timed perfectly, the birds can fatten up and be able to continue their migration. It’s such an important part of the birds’ migration to stop over here.”

Tagging and survey

Hanlon said the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been doing the tagging since about 2000-01 and she has been part of the tagging and survey since 2002.

“We have the longest-running set of data from our beach,” she said. “We’re learning the age of the crabs, how old they get, how many times they spawn a season and where they’re going.” (They mature around 10 years old and can live for 20 years.)

When people find a tagged horseshoe crab, they send the information to Fish and Wildlife and receive a certificate in return.

She showed some certificates to the volunteers. One was for a crab tagged 10 years earlier that returned to the same beach.

“We’ve also had crabs that were found down in Maryland and up in Connecticut. So not only are they being found in New Jersey again, but they’re going to other beaches pretty far away.”

“It’s really fun to see such a big group of people come out for nature,” Hanlon said of the volunteers. “People love to get their hands on animals and it’s just great to see the camaraderie.”

In some cases it’s a family affair. She met one young man who came out tagging with his parents years ago and now is coming with his children.

“It’s neat to kind of see that different generations are coming out and experiencing this,” Hanlon said.

She explained the tagging is done at Kimbles Beach because it’s close to the Fish and Wildlife office, it’s easily accessible and because Delaware Bay has the largest population of horseshoe crabs.

The dates in May and June are chosen because they correspond with the new and full moon and high tides that are closest to 8 p.m.

Getting volunteers involved is important in two ways. The first is because of sheer numbers — the group tags 500 horseshoe crabs each of the nights, a task that couldn’t be handled by the Fish & Wildlife staff and the two interns from the American Conservation Experience. (See related story.)

“If we did that just with staff, it would take us hours and hours and hours and hours,” Hanlon said.

The other aspect is increased awareness about the National Wildlife Refuge and the plants and wildlife in the 13,000 acres in Cape May County.

“Sometimes it’s the first time ever being around a crab and because they live here, there’s always great things to learn, neat things about the environment where you live,” Hanlon said. “Not only is the public enjoying it and experiencing it, but it helps us to get the tags out.”

She added that the more people who know about the tags, they more likely that they will look for the tags and then call in the information, helping Fish and Wildlife with the survey.

To sum up her work as a wildlife biologist, Hanlon said her job is basically to survey the land, know what wildlife is using the property and make the habitat better for them. It includes surveys for birds including the piping plover and American oyster catcher, and controlling invasive plants.

She explained that invasive plants can take over, so cutting them back — “a big job” — will let native plants succeed and be better for the environment and wildlife.

Hanlon said she loves her work. Tagging horseshoe crabs, she added, makes for a fun night.

By DAVID NAHAN/Cape May Star and Wave